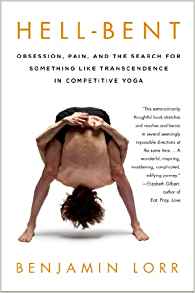

I am in mourning because yesterday I finished Hell Bent, a book I was totally taken up with, totally lost in the author’s tale. And now it’s over, I can never visit that world for the first time again.

Benjamin Lorr was at one time, if you like, a Bikram Kool-Aid drinker, who went to two 90-minute classes a day for months before joining the Backbenders advanced yoga workshop, before becoming an itinerant yogi-journalist, before attending Bikram’s 9-week long instructor’s training, and finally, before visiting various studio owners and early Bikram insiders and dragging out some intimations about the hot yoga founder’s indiscretions, some time before the big-blow-up of Bikram (a ‘la Bill Cosby) that began in 2016.

This book is both memoir and investigation, journalistic interview and a yoga history lesson. Lorr describes his own progress from yoga-zealot true believer to yoga-realist, and suggests at the end of the book that yoga is, like life itself, what you make of it — not a panacea. He tells a bit about yoga’s Indian genesis, yoga’s physiology, yoga’s different branches — of which two, ashtanga, which Lorr describes as a predominantly meditative tradition from around 200 AD, and hatha, a twist-your-body tradition created by crazy yogis of the Indian woods dating from about 1000 years later, strike me most powerfully. He talks about Bikram Choudhury’s teacher, Bishnu Ghosh, and the original 84 posture series of yoga asanas, or poses, that Ghosh documented, from which Bikram took his own rigid prescription of 26 for his beginning workout.

Taking Los Angeles by Storm

It was the efficacy of the 26 posture workout, undertaken at over-100-degree heat, that led to Bikram’s taking Hollywood, and then the rest of America, by storm, starting in the early 70’s. Bikram’s own self-narrated story, in which he claimed being the yogi who taught President Nixon yoga in Japan, and to have worked with NASA training astronauts, had to be toned down after the internet made fact-checking possible, but nevertheless, Bikram has never stopped being an iconoclast.

Lorr’s strategy here is to present Bikram as he claimed to be and was, and let the reader judge what to make of it. Lorr presents the yoga and yogis through journalistic reporting and does the same.

The most poignant part of the book is where Lorr visits previous practitioners of Bikram’s inner circle who have modified their practice and backed off from their close associations with the yogi. For various reasons. When questioned why, the answers are muted but seem to infer too much absolutism, paranoia, and controlling behavior, plus certain largely unmentioned examples of exploitation of the inner circle.

In Short, Cult-Like Behavior

I don’t remember Lorr using the word “cult” to describe the Bikram inner circle, but the suggestion of cult-like behavior is there.

This has been a phenomenal book to read while doing a 30-day Bikram yoga challenge. As I come home, sweat soaked and bleary eyed, and wonder why I am doing this, Lorr’s narrative presents a comforting and engaging diversion. Obviously, the path I am treading is one many have trod before.

Still, after Lorr’s description of Bikram’s teacher training program, I know that I could never do that part of the deal. Apparently, it involves not only dual daily yoga workouts and posture clinics, but staying up until 4 a.m. to watch movies, with Bikram, who sits on a throne as a kind of “prom king of the apocalypse.” The apocalypse being the absolute burn-out and burn-down the student-teachers undergo to be qualified Bikram instructors.

The Tale of Tony Sanchez

The book ends with Lorr visiting Tony Sanchez, one of the guru’s best-known students, someone who has his own instructional videos and association. Sanchez was told to leave the Bikram entourage years before, at his own birthday party in 1984. “No hard feelings,” Bikram said, after firing him from his job. Years later, when Bikram discovered that Sanchez was making his own set of yoga videos, he became hysterical, yelling that Sanchez would “die soon.”

Sanchez went forward with the project, moved to Mexico, continued perfecting his practice, and refused to become negative, suggesting that each yoga practitioner must follow his own path, and find his own practice.

The Problem with the Western Approach to Yoga

Part of yoga is being in the yoga, the yoking of mind and body. Perhaps the “error” of the western yoga practice is in the belief that through perfection of asana we can achieve perfection of character. We are yogi, perhaps, but we’re still humans. We should never assume that by doing yoga we can find the fountain of youth, the meaning of life, or any other terminal transcendence. The joy is in the journey.

I feel a peace of understanding Lorr at the end of Hell Bent. We need a journey, and we need stories. The journey and the stories are the yoga, the work, of our life. If, as Lorr seems to suggest, the feeling of transcendence is only partial or temporary, well, what did we expect? This like what my old friend Sheryl, from college, memorably said to me one morning in LA back in the 90’s, when we were talking about life being basically good. “How is everything,” I asked.

The book ends with Lorr admitting that he practices his yoga at home now, by the bookshelf, but still sneaks off to the hot studio nearby when he can. There is something in that hot room — putting yourself through the gauntlet, feeling you’ve survived, I don’t know what.

“Well, fine. But you know, there are always issues,” she said with a wry smile.

There you go. Yoga or no.

More Hot Yoga on Susan Taylor Brand:

The Best Hot Yoga Towel

A Brief Evenhanded Biograph of Bikram

Yoga Archive

Love when I get lost in a book!!

It was a phenomenal experience.

This one one of the best book reviews I have ever read. I got lost in you getting lost in your reading journey- and I loved it.